LLMs as a Tool for Liberation

Despite all their issues, LLMs give me the first glimmer of hope I've felt in a long time.

Large language models have brought us man-made horrors beyond our comprehension. They hallucinate and affirm facts which are untrue, and can veer dangerously sycophantic while mimicking the appearance of intelligence. They can induce psychosis in users and fail to properly safeguard the mentally ill or vulnerable. They enable astroturfing and the spread of disinformation with interactive language that is nearly indistinguishable from human writing (save some easily fixed tells). They consume mind-bogglingly grotesque amounts of water and energy to run while contributing to the homogenizing "ChatGPT-ification" of culture, most of which is powered by stolen data and used to displace human creatives and eliminate jobs. On top of all that, the exuberant market speculation on AI is spearheading a massive financial bubble whose inevitable explosion could eclipse the 2008 financial crisis.

So, yeah. All my homies hate large language models. And yet, despite all these issues, I believe that large language models are a fundamental tool for liberation. In fact, not only does the proliferation of LLMs not make me despair; it gives me the first glimmer of hope I've felt in a long time.[1]

Water

@tonystatovci First video of the year 😎 / links in my bio check me out 😎

♬ original sound - TONY STATOVCI

hilarious and untrue

Before anything else, we need to talk about the water usage problem. LLMs use a significant amount of water and energy, and it's important to understand how and the nuances of their resource consumption. However, the resource picture painted by most critics of AI tends towards the hyperbolic, whether out of fear, poor methodology, or motivated reasoning.

I found the energy panic which followed the popularization of cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin, to be instructive. At the end of 2017, Newsweek published projections put forth by a Digiconomist paper that Bitcoin mining was on track to consume all of the world's energy by 2020. Contemporary pushback was immediate. It was pointed out that the founder of the Digiconomist, Alex de Vries, had been hired a year prior by the Dutch Central Bank, with a specific focus on "Financial Economic Crime". This paper and others by Digiconomist/de Vries/the DNB had outsized impact, even directly cited many times by the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy 2022 Crypto Assets and Climate Report (direct link no longer available on whitehouse.gov).

According to the Cambridge Bitcoin Electricity Consumption Index, as of 2025, the global energy usage of Bitcoin (the main computationally hungry cryptocurrency) currently sits at an estimated ~200 TWh (Terawatt hours) per year, which amounts to a thankfully less apocalyptic ~0.6% of global electricity usage per year, and powers the financial infrastructure for ~$3.3 trillion (about the GDP of France, the 7th largest country in the world). Still, almost 1% of the entire world's energy usage may seem alarming, but the CBECI's Comparisons page is helpful for putting this in perspective. Using roughly 2018-2020 data (the most recent available for numbers other than Bitcoin; current numbers will be larger), data centers were measured to consume 200 TWh in electricity per year; TVs, lighting, and fridges consumed a combined 224 TWh; global iron and steel production consumed 1233 TWh; and global air conditioning consumed 2199 TWh. There are many things you can criticize cryptocurrency for (and should), but a world ending quantity of energy usage is not one of them.[2]

And most people I talk to still don't know this! You never hear about cryptocurrency anymore, not because we defeated the energy hungry beast known as Bitcoin (crypto usage continues to rise), but because it was never that significant of a concern. It was adopted and integrated into the existing financial systems, iterative technical fixes to reduce energy usage were made over time, and once NFTs left the cultural stage, people didn't care to check whether cryptocurrencies were actually dead or not. We were just relieved those expensive monkey JPGs were finally gone.[3] An initial misconception provided fuel to well-meaning (but incorrectly directed) anger and concern, people immediately made up their minds about it, swore to never interact with or investigate the technology, and that technology continued to slowly develop until it became a part of every day life, even if people didn't notice.

Large language models

So, large language models.

The dominant narrative is that large language models consume, to use a technical term, oodles of water. How many oodles, though, is contested. A common way to measure water usage is by the usage for a single "query". In 2025 Google claimed a single Gemini query uses 0.26 mL ("or about five drops"), Sam Altman claimed the "average" query uses 0.32 mL ("roughly one fifteenth of a teaspoon")[4], while in 2023 the UC Riverside paper Making AI Less “Thirsty” found that a query consumes 10-100mL per query, dependent on location (~16.9 mL on average in the US). This paper was based on GPT-3, an older and more energy hungry model.

Now, coverage will often talk about "usage", but you need to distinguish between withdrawal (water being temporarily removed from a source and returned to the system, such as for liquid cooling systems) and consumption (water that is lost through evaporation, contamination, etc.). The UC Riverside paper projected that by 2027, water withdrawal for LLMs would be 1.1-1.7 trillion gallons per year, but water consumption is only 100-158 billion gallons, about 9% of the withdrawal figure. That still sounds like a lot, but global annual freshwater withdrawal is ~4,000 billion m³ (roughly 1.057 quadrillion gallons), of which 1.1-1.7 trillion gallons is about 0.1-0.17%. Global freshwater consumption is not as easily tracked, but in comparison the amount of water consumed by LLMs would be similarly negligible. Andy Masley has done a thorough analysis of the environmental impacts from AI usage, mostly based on the old 2023 data which doesn't account for dramatic improvements in LLM energy efficiency. (Here's another more up to date breakdown, updated for August 2025.)

Masley illustrates the water usage of prompting like this:

Have you ever worried about how much water things you did online used before AI? Probably not, because data centers use barely any water compared to most other things we do. Even manufacturing most regular objects requires lots of water. Here’s a list of common objects you might own, and how many chatbot prompt’s worth of water they used to make (all from this list, and using the onsite + offsite water value):

- Leather Shoes - 4,000,000 prompts’ worth of water

- Smartphone - 6,400,000 prompts

- Jeans - 5,400,000 prompts

- T-shirt - 1,300,000 prompts

- A single piece of paper - 2550 prompts

- A 400 page book - 1,000,000 prompts

If you want to send 2500 ChatGPT prompts and feel bad about it, you can simply not buy a single additional piece of paper. If you want to save a lifetime supply’s worth of chatbot prompts, just don’t buy a single additional pair of jeans.

Of course, fear generates clicks, so sensationalist headlines and TikTok ran with unqualified and often exaggerated numbers from the UC Riverside study, and now people think asking ChatGPT a question takes as much water as flushing your toilet. I think the truth is probably somewhere in the middle. There are many more nuances to consider in an in-depth discussion about data centers and water usage in general, but LLMs are not going to drink us dry globally.

You, me, and data centers

We also need to talk about data centers. As of 2025, there are roughly ~6,000 data centers in the world, with the majority being in the US. People are rightfully mad about them, because they are causing harm to real human communities and natural environments due to their local impacts. Musk's xAI (Grok) data centers are causing direct health impacts to black communities, Google was recently exposed for being possessive of over a quarter of the city of The Dalles' total water supply, and in general, data centers use groundwater, where the main issue with consumption (despite being a relatively minuscule amount of total withdrawal) is that they gradually evaporate the water into the sky, permanently leaving the local water system.

But here's the thing: they're supposed to go in a fucking field! They're not supposed to be built that close to people! And we have ways to significantly increase water efficiency in data centers and reduce impacts on local water tables. In fact, companies building data centers have known about power and water usage problems since as early as 2007, when a consortium of the largest tech companies of the era founded The Green Grid, who proposed the Water Usage Effectiveness (WUE) metric in a paper in 2011. In 2014, data centers in the U.S. took up about ~1.8% of total US electricity consumption [5], but in 2016 fewer than one third of surveyed companies were tracking water usage[6]. As usual in technology, it's been a mad rush for data, power, and power.

Besides pure corporate avarice, there are other factors that also influence their placement. To name some:

- Power grid and fiber data transfer infrastructure, both of which are extremely expensive and time-consuming to build in new locations, tend to be located near people[7]

- 36 states offer tax incentives to data centers, some offering 20-30 year exemptions[8]

- Land is cheaper where lower-income communities live, making them financially enticing to companies[9]

- Zoning laws tend to be more ambiguous in less developed areas, making already developed areas more appealing[10]

- Proximity to users and companies has a direct impact on load speed and performance[11]

Basically, it boils down to the fact that the infrastructure is where the people are, and building new infrastructure is expensive. (Oops, I guess it was corporate avarice after all.) Of course, all of this is downstream of the fact that we lack regulation. There are known ways to improve water efficiency, such as closed-loop cooling systems that reduce freshwater use by up to 70%, various water-free cooling approaches, immersion cooling, and undoubtedly more as we do more research. But all of these are voluntary; it is entirely up to the good will of a corporation to follow these rules. And they say they're going to! In 2020, Microsoft pledged to become "water positive" by 2030, and Facebook and Google followed suit in 2021, as did AWS in 2022. But can they be trusted? We just caught The Dalles suing local news outlet OregonLive (presumably on Google's behalf) to not disclose Google's data center water usage there.

Boycott everything

So, what's one to do? Certainly this administration is not going to stoop to the humiliation of safeguarding the interests of its people against corporations, at least at a federal level. So we vote with our wallets and boycott, right? All my homies hate data centers. Except that unfortunately, you, me, and data centers have been complicit in increasing energy and water use for at least a decade. As of 2024, AI workloads (LLMs, image generation models, visual recognition, and other models combined) took up roughly 5-25%[12] of total data center workloads, meaning that the rest of it is everything else. What's everything else? As a thought exercise, let's pretend we are going to boycott data centers--specifically the huge ones they call "hyperscaler" data centers.

First, we need to get rid of the obvious stuff: no ChatGPT and no AI tools. That's easy. Google is increasingly slop-ifying their search with AI stuff now anyway, so let's just switch to DuckDuckGo.

Next to go is streaming, of course. Netflix, Spotify, YouTube, podcasts, all must go. Video streaming makes up 65-80% of all internet traffic, so that's great. Social media, of course--that's actually a relief. Instagram, Twitter, TikTok, Reddit, Facebook, gone. We uninstall Uber or Lyft alongside UberEats and Doordash or whatever apps and get our steps in eating local. E-commerce has to go--Amazon, Etsy, eBay, but also the small local stores you want to support--they're hosted on Squarespace or BigCommerce or some other massive e-commerce platform. It's OK, we can walk there. We'll learn our neighborhood like the back of our hand, which is important, because we also cannot ethically access any map apps, weather apps, or any major metropolitan transit system (NYC and London metros use AWS, for example). If we're driving, we would avoid most modern cars after 2015, as well as any cloud-loving insurance companies. Of course, you can't use most popular websites, or any email service you can't verify isn't hosted in a data center. (So probably no DuckDuckGo after all, unfortunately.) You can save the money on the new planned-obsolescence-ly smart phone and get a dumb feature phone instead. Those are just the conveniences, of course. Not that we were going to the hospital anyway (too many of them use AWS), but we should have a list of insurance providers we avoid too--UnitedHealth, CVS Health / Aetna, Humana, Elevance, to name a few. You would need to carefully choose your bank, making sure they don't use a cloud provider (and many of them do), and have a reliably open branch near you, because you won't be able to use an ATM. Visa and Mastercard operate their own private equivalent hyperscale-class data centers around the world, and both debit and credit cards run through that processing network. So, cash it is.

This, of course, is the extreme version of boycotting data centers. There are some true sickos (positive) out there who would, can, and do live this way. I respect and fear them. After all, the Amish exist, and they've just kept doing their thing far away from all of our chaos. But the moderate version is still incoherent, because where there is software there is data and where there is data there are data centers. This is a fact of modern life; modern convenience is dependent on having a place to store the data and functionality which facilitates it. If tech corporations acted responsibly, we would never hear about it; these things by and large (are supposed to) make things easier. The technology itself is neutral and can be deployed in environmentally conscientious ways.

But let's say we did want to try to take a reasonable, moderate stance. No harmful data centers. How do you even boycott data centers, like, pragmatically speaking? Do we demand to know which availability zone[13] every company we shop at is in? It's standard practice to distribute your application across multiple availability zones to improve stability and achieve faster load times for people closer to their respective zones anyway, so that doesn't really work. Which data centers count? Do the private ones run by Visa and Mastercard get a pass because they're convenient? Do we choose based on cloud providers we don't like? Do we boycott a local restaurant (a notably low margin business) because their landing page is hosted by a website host that uses AWS? Do we decide on tangible value? The bank and health statements can stay, but all the personal photos and file backups must go? These questions sound silly because they don't really fit the shape of the problem.

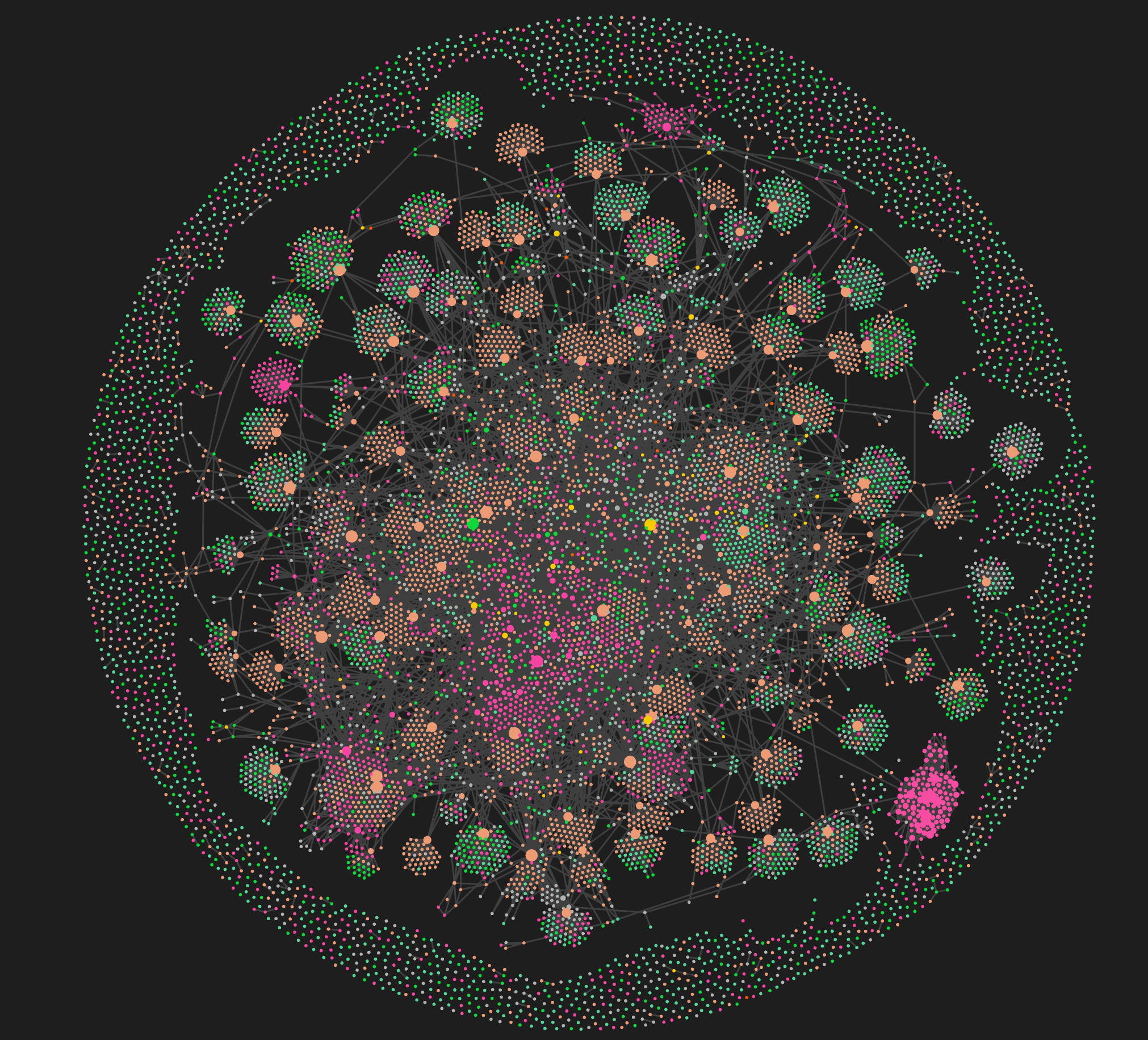

Technology companies, data centers, the power grid, and networks of information have infiltrated modern life at every angle. We are at a stage where all of it has swirled together into the structures with the capacity for it. You can make your case about how good and bad this has or hasn't been, but my point is that at this point, it's all swirled together like water. I don't think it makes sense to try and identify which flow of water belongs to who--instead, treat it as it is, like a public good. I believe that data centers should ideally be treated as a public utility, with strict regulation on their locale, construction, and water use efficiency targets. (I also believe that hosting and internet access should be a fundamental human right in the modern era, and that every human should have free digital storage access, but that's a different essay.)

I'm not holding out for a sudden awakening of conscience from our federal government or tech companies, but we are seeing public action at a local and state level making a meaningful difference to slow the deployment of data centers. Over 142 activist groups across 24 states have managed to collectively block or delay $64 billion worth of US data center projects. This seems to be spearheaded by the Virginia Data Center Reform Coalition, formed in 2023 to examine data centers' impacts on human and environmental health. For this critical moment of global resource contention, going slower (or stopping entirely to reconsider) is a very good thing.

As more people connect to the internet and demand increases, we do need data centers. Not just for the stupid things we hate, but also the nice things we love. There is a correct way to build data centers, activists and organizations who care are working on solving the problems, and the companies building them at least pay lip service to the idea of solving the problems. If you're interested in getting involved yourself, you could check out environmentalist organizations like Sierra Club or Clean Water Action.

So, with all that being said... projections from previously linked studies do expect that AI model usage will account for 35-50% of data center capacity by 2030. It's hard to say what fraction of that would be large language models, but just on vibes, probably at least half. If you haven't checked in on LLMs since you heard they were dumb and bad in 2023 (which, they were), this might make no sense to you. Surely we can't kill the internet that much more dead with AI, can we? (I mean, of course we can.) But the demand is there because these things are insanely, frighteningly good, and they're only getting better. Amidst geopolitical strife and massive socioeconomic disparity, I believe that large language models will play a key role in changing how society, communication, and capitalism function at an individual and collective level, and not just in a bad way.

But first, I probably need to catch you up. Hey ChatGPT, how many R's are there in...

Strawberry

@michaelbonvalot 🔴Wie ChatGPT drei Minuten lang daran scheitert, das Wort Erdbeere (Strawberry) richtig zu schreiben. Dabei behauptet die KI auch noch durchgehend, dass sie mit ihrem Müll recht hätte. Schaut euch das an - und bitte passt immer extrem auf, wenn ihr KIs verwendet und prüft die Ergebnisse!

♬ Originalton - Michael Bonvalot - Michael Bonvalot

original source on instagram by zack_telander (embed didn't work with direct link, sorry)

"Revolutionary technology?" the skeptic might be saying, "The thing that confidently makes things up and can't count the letters in 'strawberry'?"

And that skeptic would be right. Large language models are bad at these things. That's not what they're for. I think that since LLMs are a novel technology, we default to judging them according to what we already know: computers. But computers are number machines, made of binary values at the lowest level; large language models are language machines, made of massive multidimensional layers of word associations. Spicy autocomplete, if you will.[14] Their fundamental nature is probabilistic, and their functioning shares the same essentially ambiguous and wiggly nature of language. As a result, they have two key limitations: they are susceptible to hallucination; and they can sometimes fail to follow instructions correctly. But around those limitations there's an entire world of fuzzy information and language that doesn't need to be handled absolutely perfectly. Each new wave of models shows better and better performance, making fewer mistakes and hallucinating less. The current occasional issues can be handled routinely with software guardrails and good prompting.

Large language models are leaps and bounds ahead of where they were in 2023 when they began to enter public consciousness. The frontier models currently available (particularly Anthropic's Opus 4.5 model) are, in my opinion, finally at the level of intelligence and reliability that users were expecting when LLMs first became commercially available. They can follow complex multi-step instructions, synthesize information, do high level abstract reasoning and apply mental models to problems, perform competent language translation, iterate on processes and self-reflect, and they can do all this while juggling dozens of variables embedded in hundreds of thousands of words of text. They can't make novel insights, but you can have them produce iterative combinations of ideas that humans (and often fellow reviewing LLMs) can quickly sort through to pick out the valid ones worth further exploration. On top of all that, they can do this from a single request in natural language that doesn't even have to make complete sense, and they never get tired or discouraged.

These language machines aren't for counting letters, recalling facts 100% of the time, or crunching huge amounts of data. They're for everything else you do with language. And it turns out there's a lot of everything else. Anything that has to do with text or language, an LLM can probably help with, either directly or somewhere in the process. I'll give you some examples, moving from simplest to the most complex. All the examples that have links to sample conversations were done with Sonnet 4.5 on the $20 Claude Pro plan. I'll mostly be talking about Anthropic models, since I currently prefer their models the best.

If you've had experiences with large language models performing terribly in the past and are surprised by what I say they can do below, it's important to keep in mind that the model really matters. The frontier models (Sonnet 4.5, Opus 4.5, Gemini 3 Pro, and ChatGPT 5.2) are the only ones that approach my estimate of, like, 90% trustworthiness to complete most common tasks effectively. If you've never used an LLM before and want to get something real done, don't even bother with the older models, quite frankly.

For Anthropic's $20 plan, you can expect about 50 Sonnet 4.5 messages every 5 hours. For occasional use throughout the day, that's plenty. For vibe coding or doing document-heavy work, that's nothing. The $100/month and $200/month plans are the best bang for your buck, providing much more usage, and as you'll see below, absolutely worth the sticker shock if you do a lot of work that LLMs can help with.

How well an LLM will perform also depends highly on scale. Don't expect an LLM to be able to process a document that is larger than its context window, or send more than a couple messages about a document that takes up 90% of the context. Very large tasks need to be broken up, but there are strategies for doing this with agents--covered later.

Core language model capabilities

Here are some of the "basic" fundamental tasks that LLMs can help you with:

- Basic text reformatting - many extremely cheap and fast models can do this perfectly now. Cleaning up text, formatting it into bullet list format, tables, or vice versa. If there's a tedious and mindless text editing or transformation task you find yourself doing, there's probably a way an LLM can automate that for you. You don't need frontier models for most of these sorts of tasks, but Sonnet 4.5 will do any of them perfectly.

- Organization, restructuring, and summary - LLMs can reorganize a stream of consciousness thought into a coherent document, pull out key facts, figures, and deliverables from meeting notes, or summarize key ideas and points from a long essay, with source verification[15], for example. You can also use them to generate diagrams, either in old school ASCII or by having it generate a Mermaid diagram.

- Knowledge, research, and fact-checking - while LLMs still can hallucinate (and you need to check their claims if it's for anything important), generally speaking their recall from known/common sources like Wikipedia is extremely good, and the solve is to simply have them look the information up. They can search the internet, scan webpages, and search through PDF documents. They can help compare and verify facts and claims, extracting key details, and synthesizing information. You can use them to compare key numbers and claims in an intentionally complex health insurance brochure, for instance, or across multiple different plans.

- Education and learning in known domains - LLMs are actually excellent teachers for solo learning, because you can ask them a million questions about different angles of a problem. At enough specificity and niche questioning you will absolutely find the edge of the model's knowledge, but it's a massive help for getting started in a new space. Being extensively trained on STEM materials, they're especially good for learning those topics, and they can check their own work by running code directly.

- Problem-solving and analysis - you can have LLMs apply mental models or analysis frameworks to different problems, such as weighing pros and cons of different plans or performing a SWOT analysis. They can act as sounding boards for ideas, and also give you reality checks on feasibility or drawbacks. (You have to make sure to ask for those, though--or add that instruction to the LLM's system prompt.) I find them especially useful for food-related problem-solving like figuring out what to do with what I have in the fridge, scaling recipe ingredients for different numbers of people, and planning shopping lists.

- Writing assistance - I don't let LLMs write for me, but frontier models can provide high-quality proofreading, error-checking, and tonal advice. I've started to leverage LLMs as a core part of my workflow for research-heavy essays. I use them to organize outlines, help me kick around ideas, research and verify key facts and figures, and help me rhetorically structure arguments. I use them to find places I've left myself TODO notes in my sprawling essays, reorder footnotes I inserted out of order, and spot flow issues across the essay, whether grammatical or structural. But even beyond that, they're especially useful for writing form letters. More on that later.

- Translation - LLMs can provide very serviceable translation for every day use, although it depends on which languages the model's training focuses on. I have used LLMs to navigate legal situations in foreign languages, mostly for reading documents and being able to communicate in exchanges. Of course, there's no way to verify the quality of translation myself, so I don't rate this one too highly, but it definitely lets you communicate, and even specify the tone you want to take in the process.

To be clear, LLMs are magic language machines, not silver bullets. You still have to learn how to use them effectively and work around their intrinsic limitations. These workarounds are quickly becoming standardized best practices among users and organizations using LLMs which make LLM outputs highly reliable.

Of course, all that's the boring stuff.

Visual models, speech-to-text, and accessibility

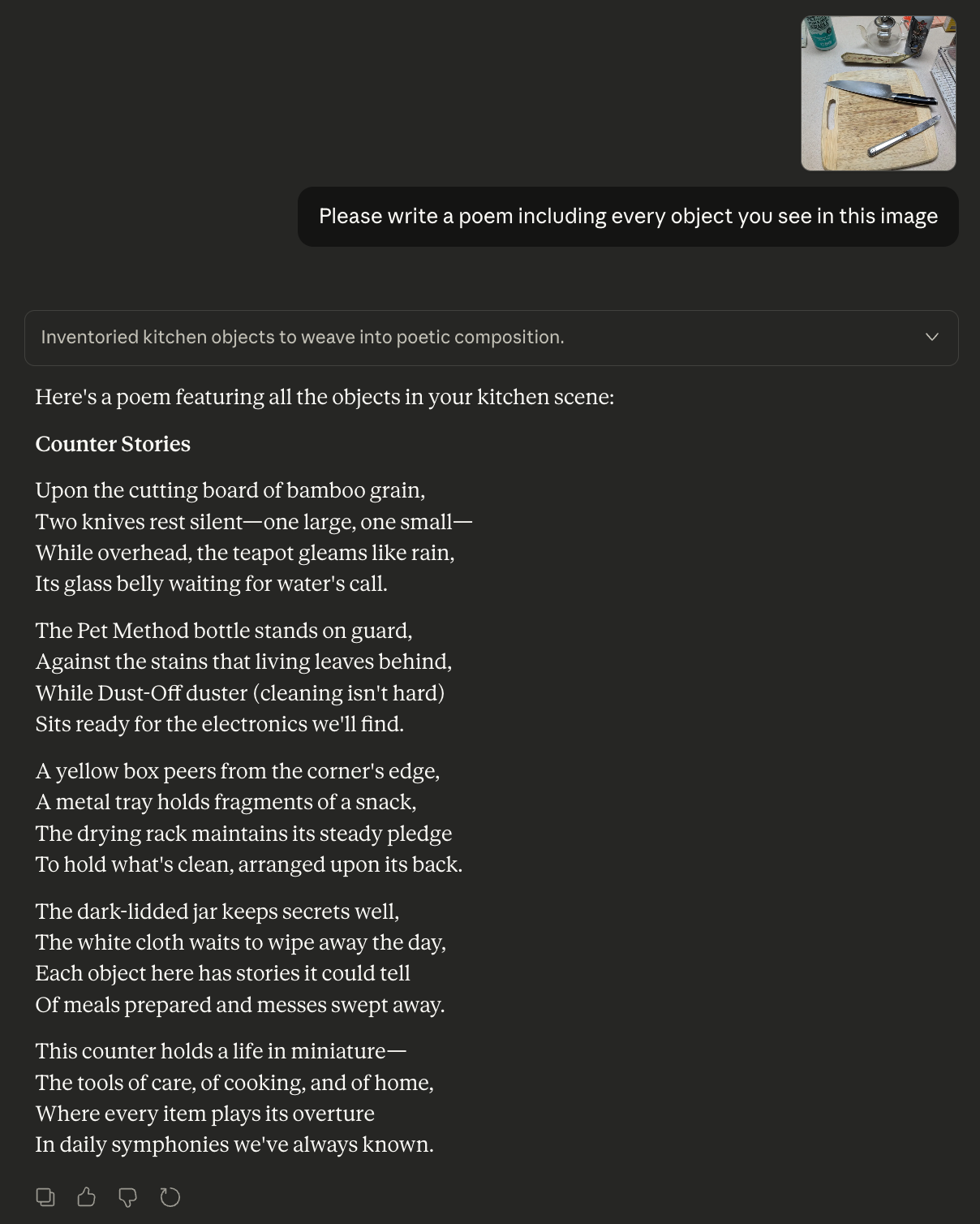

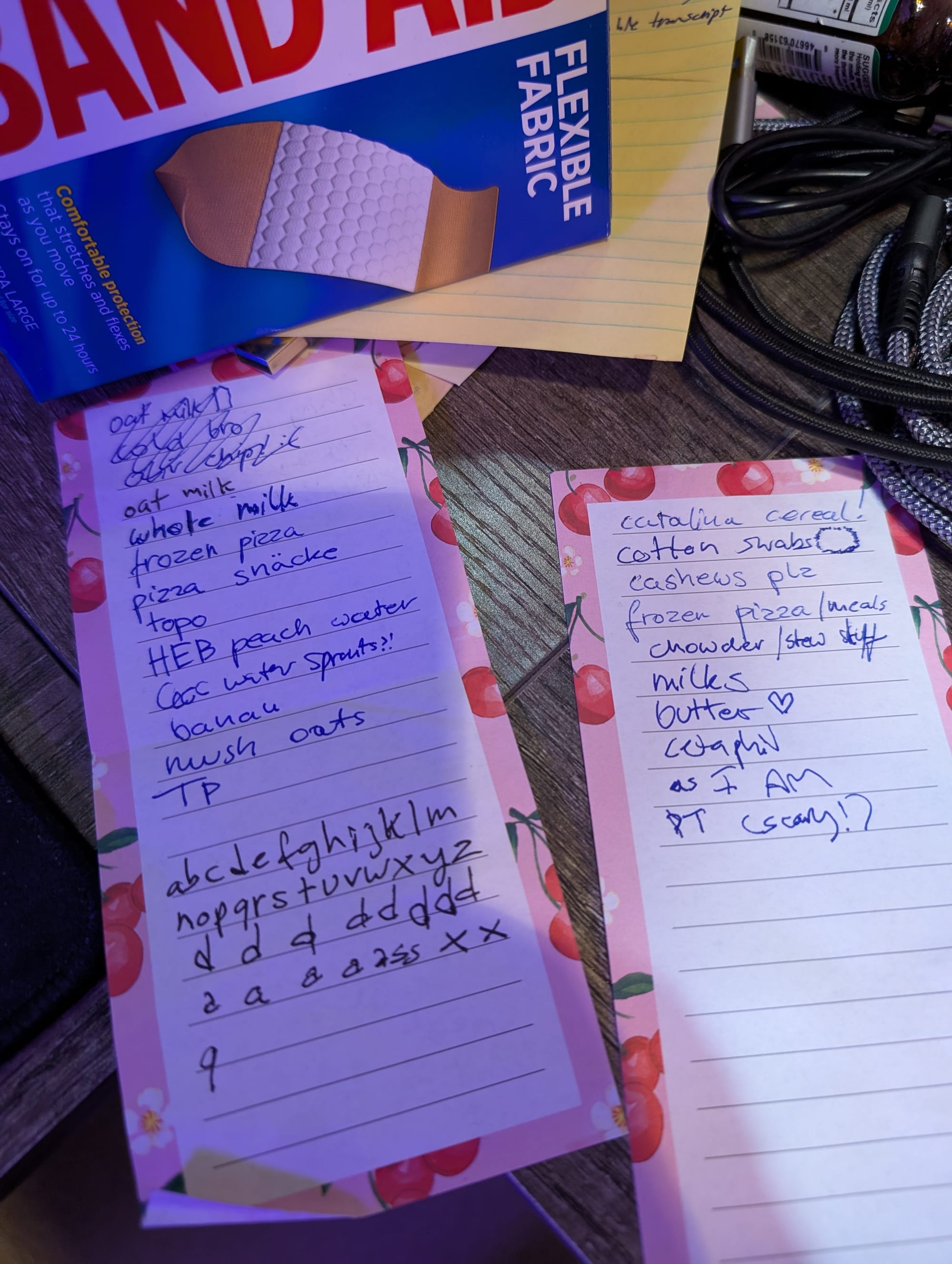

Let me not bury the lede too far here: a hugely useful addition came out of large language models, which is language-driven visual models--not the image generation ones but the ones which can actually view, understand, and describe arbitrary images. I've used this in foreign countries to navigate appliances with different functionality in languages I can't read, for instance. The model could not only view the photo, but also read and simultaneously translate the language, and even search for information on the specific model.

They're not perfect, but they're quite good, especially for reading messy handwriting, which is one of my most frequent use cases. These visual models can read your messy journals (up to a certain extent, of course) covered in diagrams and margin notes and drawings and ink stains and shadows and it can read out much of it--far more than traditional optical character recognition models can. Ironically, knowing that I have access to visual models to digitize my journals when I get around to it has actually made me feel freer to write on physical media again rather than keeping everything digital to avoid the rote work of tediously digitizing and OCRing all of my notes page by page. The really cool thing though, is that since these are dual visual-language models, you can actually give them instructions about what to do, what parts to report and ignore, etc. I'm not sure how much I trust this combo of complex instructions and visual recognition yet, but it has plenty of potential as the technology improves.

Another way visual models factor in is in LLM-driven computer usage, which is as scary as it is exciting. This is exactly what it sounds like: an LLM uses a visual model to read the screen on your computer, think about it, interact with the computer, and do tasks for you. This recently came out for general usage in Anthropic's Claude browser extension but it's quite slow. I found it underwhelming. Still, this technology is coming, and it'll be usable enough for various tasks before we know it.

While speech-to-text models are nothing new, they're reaching a new level of effectiveness and flexibility. In 2022, OpenAI released a next generation open source voice-to-text model called Whisper. This model is good enough that you can really ramble in an open-ended way and it will capture sentences, figure out quotation intent, and generally handle interrupted, sloppy, or unclear language. This open source model can be included straight into the frontend of websites and is efficient enough to run on-device, which means you will see fast and easy voice transcription in more and more apps.[16]

The combination of large language, visual recognition, and speech-to-text models together actually represents a huge step forward for accessibility. By providing a diversity of ways to interact with software and produce text, this can help people with motor, sensory, and cognitive disabilities use technology. People who cannot easily physically manipulate computers or experience pain using devices are going to have increasingly expressive ways to control them via voice. Screen reader technology will improve massively for those with impaired vision, since visual models can help convey contextual importance in a way traditional screen readers cannot. It will remove the task of having to scroll through a page of irrelevant information, because users will be able to jump straight to the tasks they need to on any website just by describing the task to an LLM with a vision model.

Even as a relatively able-bodied person, speech-to-text models and LLMs have been a godsend for sparing my fingers from repetitive stress injuries. As someone who works in software professionally and has many side projects, I am at a keyboard most waking hours. With chronic typing, clicking and dragging, copying and pasting, switching between keyboard and mouse and so on, there are hundreds of little tiny movements daily that add up. Over time this resulted in occasionally seriously productivity-impeding aches and pains in my hands and fingers. I have decades of software left ahead of me, so this has been a serious concern--but being able to speak to my computer and also no longer have to code directly myself has made an immediate improvement on my physical well-being.

LLMs can help those with dyslexia, autism, or language processing disorders by aiding reading and tone comprehension, processing ambiguous language, and iteratively finding the right language for self-expression. They're incredibly useful for people with ADHD and cognitive disorders or trauma. They can break down tasks, remind you of the key focus, offer encouragement or perspective, and with integrations, can even be configured to independently remind you of things and help with task management. And yes, it's grim to say, but with the current state of US education, I expect that LLMs will play a significant role in accessibility for the next generations' illiterate populations.

Navigating systems with expertise

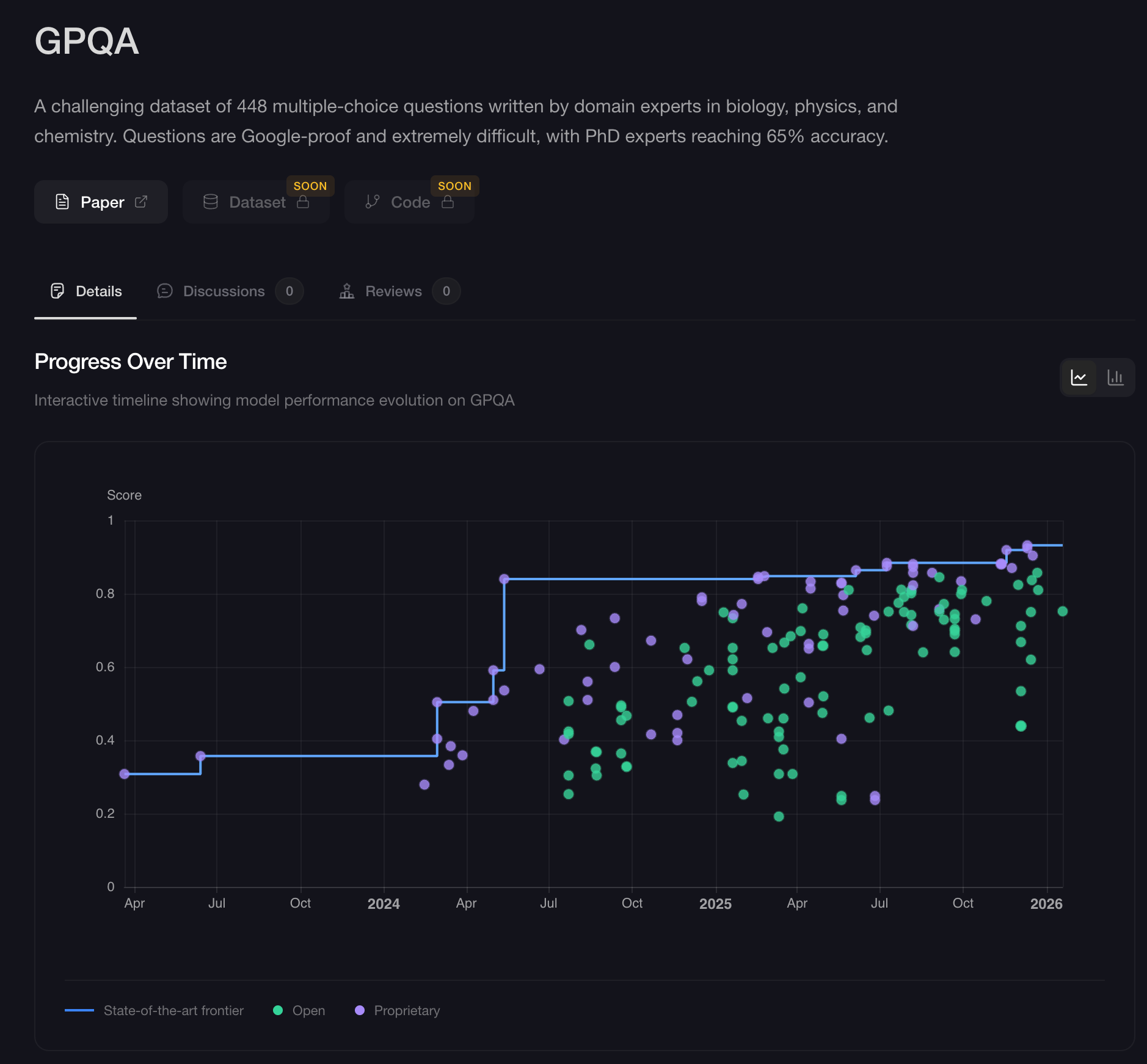

None of this even mentions the real-world performance frontier models are seeing across STEM and legal realms. The GPQA, or Graduate-level Google-Proof Q&A, is "a challenging dataset of 448 multiple-choice questions written by domain experts in biology, physics, and chemistry. Questions are Google-proof and extremely difficult, with PhD experts reaching 65% accuracy." While LLMs do not possess true insight, they can be instructed to carry out insight-producing processes. LLMs can apply mental models or seek out connections and iteratively work through problems from multiple languages, applying permutations of ideas and potential solutions. This approach is leading to breakthroughs in mathematics and medical research and diagnostics. The LLMs don't have to be smart enough to do experts' jobs--they just need to be smart enough to help the experts catch things they might otherwise miss, or tirelessly carry out mentally laborious yet ultimately uncreative tasks.

As of this January 2026, OpenAI's GPT-5.2 leads at ~93%, Google's Gemini 3 Pro scored 91%, and Anthropic's Opus 4.5 scored an 87%. These frontier models are scoring high marks in software, medicine, law, and there are endless benchmarks you can find online evaluating different models' skills in different domains.[17] What this means for the every day person is that suddenly, they will have help navigating complex systems, parsing dense legal language, and researching and understanding the law.

I have an immediately relevant personal example of how this helped me. In a house I was renting last year, the property management company failed to repair two different instances of utilities failing--A/C barely working approaching peak summer temperatures, then the hot water heater breaking--and then failing to be repaired for a cumulative 65+ days between the two. Each took over 30 days to be addressed, and during the second utility failure, I never spoke to a single human being from my property management the entire time. Ironically, they had used some sort of terribly implemented LLM-driven maintenance concierge service that would send me infuriatingly clueless and context-less questions about the maintenance system, which I complained about to them since I could fucking tell.[18] Anyway, I could be accused of being patient of personal suffering to a fault, but somewhere around the 4th week of cold showers I finally decided I had had enough.

I used Claude (and some of ChatGPT's deep research mode[19]) to research my local state laws, the process and information I need to sue, describe the ins-and-outs of the situation, and my options. Through this process I found out exactly which laws my property management company was in fact violating, what my recourse was, and the compensation I could be entitled to if I took legal action. Of course, the final conclusion and advice was that I should speak with a lawyer (due to specific nuances of my situation involving the previous failure to repair), but I was able to find out that in fact my situation was likely to be a fairly clean open-and-shut case I could do entirely myself if I decided to sue. Now, of course, the models got some things wrong here and there and I used my human intelligence to double-check things, and they could not provide clear direction on the nuances of my case. But I am a busy professional drowning in responsibilities and obligations, and I am generally a passive enough person that I would let this go (assuming they actually finally repaired it) due to the hours of research involved. However, thanks to being able to research this with LLMs, when I was finally pissed off enough to do something, it only took me all of two hours to research and draft a Notice to Repair form letter with Claude's help, citing the specific laws that were being violated, immediate next steps, and the threat of entirely-justified legal action if the repairs were not done immediately.

The property management company called me back within 30 minutes of my sending the email (and certified letter), with frantic apologies and promises to fix it. They got the water heater replaced within 3 business days. The ball is still in my court, since they violated the law, and now both they and I know that they violated the law. So, yeah--LLM versus LLM, I guess? Good guy with an LLM? In any case, this is just one specific example. LLMs can help research and draft form letters for disputes and complaints, get a preliminary understanding of legal options, and help you self-advocate while navigating systems that are intentionally designed to be hostile and difficult to navigate.

But not just that, of course--they can help with everyday life tasks, administrative tasks, basically anything that has searchable and referencable rules, guidelines, and procedures. Lease/HOA agreements, NDAs, insurance appeals, gathering documents for bureaucratic processes, understanding all kinds of forms, and so on. You get the idea. If there's a process or bureaucracy that's stymying you--even if just the thought of handling it fills you with too much dread to do it--a smart LLM might be able to help. Obviously, if you are able to, always understand the documents and information in the situation and always consult a professional if your situation requires it. Never delegate your decision making to a language model.

It's actually deeply gratifying to me--and fitting--that LLMs can be used for the common good in this way. After all, that's how they were created in the first place.

The public commons origins of AI

Not many people unfamiliar with large language models know this, but LLMs are fundamentally open source--a practice of making software code publicly available for modification and distribution which began in the late 90s as a reaction to proprietary corporate code. While reasons for participating in open source and its particular flavors differ, at its root, open source was born out of a radically collective, decentralized ethos. Open source means that you can download software, run it, modify it, redistribute it, and do all of that for free with other people. The entire internet--really, every computer--is run in some part by open source software.

OpenAI first commercialized large language models to the general public in 2023, but Google invented them in 2017. Or rather, I should say, eight Google researchers--Ashish Vaswani, Noam Shazeer, Niki Parmar, Jakob Uszkoreit, Llion Jones, Aidan N. Gomez, Lukasz Kaiser, and Illia Polosukhin[20]--published what will likely go down as one of the most important papers in computer science history Attention Is All You Need. In it they described a novel way to process text: all at once. Previous language generation models primarily used an approach called recurrent neural networks (RNNs) which process text in a short-term, linear fashion. Instead, transformer models work by doing away with much of the technical rigamarole of RNNs and build internal associations between words across the entire corpus. This enables the emergent behavior of being able to replicate language and understand conceptual relationships encoded in language. If you know what is related to what in enough detail, eventually you can imitate the process of thought by producing the same output that humans do--language. That's also why these models are so gargantuan: they train on the whole thing simultaneously. (This is a simplification of all the details of the process, obviously.) The key thing is that this paper was published publicly on arXiv, an open-access archive for scholarly work. Google could have chosen to patent it, but they chose not to. Thus the methodology was essentially fair game for anyone who could reproduce it, and people did.

The corporations did too, of course. OpenAI began developing their GPT line of models in 2018, first releasing research on GPT-1 in 2018. They teased the existence of GPT-2 in February 2019 but refused to release it over fear of misuse, until they released it anyway 6 months later (including open source weights). In 2019, OpenAI restructured to be less non-profit and more for-profit, accepting a billion dollar investment from Microsoft. In 2020, OpenAI released GPT-3, which would be the first major model to be released commercially[21] without sharing the model publicly, because Microsoft had laid exclusive claim to the underlying model. That year, Dario Amodei left OpenAI over AI safety disputes and would go on to found Anthropic in 2021. Meanwhile, Google was internally developing its LaMDA chatbot technology; in 2021 two LaMDA researchers left Google to found character.ai because they were frustrated at Google's safety concerns, and one engineer was fired over claiming to press that LaMDA was sentient. Anthropic also finished training their first Claude model but delayed release, hoping to avoid inciting an AI arms race. OpenAI had no such qualms and released ChatGPT with GPT-3.5 to the general public in 2022, a watershed moment. GPT-3.5 was, in my opinion, the model that showed the first glimmer of what LLMs would eventually become capable of. The AI race was on.

Publishing the Attention Is All You Need paper was an interesting choice. It was commendable for Google to both publish publicly and not patent this discovery, as the effect was final and complete: they pulled the genie out of the bottle, the cat out of the bag, another idiom for something you can't undo. While corporations were taking up the tech press cycle, in the background, the open source community was also learning how to build large language models. 2023 saw a flurry of open source contributions, including by Meta, who released the open-source LLaMA model competitive with GPT-3 in performance. Mixtral released a mixture-of-experts model which was comparable to GPT-3.5 (and GPT-4 on some tasks). In 2024, Llama 3.1, Qwen2, and Deepseek-V2 were released, all approaching GPT-4 in class, and then QwQ 32B and DeepSeek-R1-Lite were released and rivaled o1-preview. In 2025, we have DeepSeek-R1, DeepSeek-V3.2 and Qwen3, which are beginning to rival o1 and GPT-5 on reasoning tasks (both genuinely powerful models).

These models are open source, which means you can technically run them yourself, today. Hardware is currently the primary limitation--these models are big and generally don't run well on most consumer hardware, but that is likely to change soon with recent advancements in LLM-friendly memory architecture with Apple leading the way. The options for using these models on consumer hardware currently are to use "quantized" (compressed) versions of the models, use an API provider that hosts an open source model, rent a GPU server, or do something fancy like distributed LLM inference, torrent-style. The trend is still towards faster, cheaper, and better, with open source trailing only months behind closed-source frontier LLMs.

If you're not ready to check out open source models (or they're not where you need them to be), I think that these tools are so useful and so powerful that it's worth giving a big AI company $20 (or $100 or $200) a month while you learn the tools. Switching out a model or agentic coding tool is extremely easy, and there is very little stickiness as long as you do not invest or get attached to your data inside their walled garden experiences. If you exclusively use Claude Code with files on your computer, for instance, you can switch away any time you're ready.

What this means is that with open source LLMs, you can run your own models either on your computer (best) or on rented resources (fine). You can have a model serving as a massive knowledge base, a personal assistant, a programmer, all on your own computer that never talks to the internet (except for things you ask for like search). You can think locally and offline-first with your model. It wouldn't surprise me if in the open source model community LLMs will come to mean local language models.

The beauty of this too is that since the methodology is public, anyone can technically train their own models. Anyone can compare whatever sources of inputs they want and train them on them. This leads to the possibility of a vast array of specialized models for different types of tasks, or models loaded with specific types of knowledge designed to serve different communities. I believe that in the future, LLMs will be treated as communal infrastructure. Not everyone needs to use one, or understand how to build or train one. But people will be able to pool resources with the help of developers (and vibe coders) to create models that serve people, not corporations.

Imagine being able to have an intelligent agent that can manage a repository of your information, for you, on your computer, not served by a corporation or a government, and it works even when the internet is dead.

Data theft and fair use

Before we go any further, we need to discuss another problematic aspect of LLMs: theft in their training sets. Initially, these large language models were trained on massive corpuses of ostensibly open-source data compilations like The Pile, which still included some copyrighted datasets--as well as some very clearly stolen data. The primary issue was that LLMs were also outputting this stolen and copyrighted data. Both OpenAI and Anthropic were sued over the outputs of this data, by the New York Times and Andrea Bartz plus several publishers, respectively.

In the landmark Bartz v. Anthropic ruling, Judge Alsup ruled that:

(1) Anthropic’s use of the books at issue to train LLMs for the purpose of returning new text outputs is “spectacularly” transformative and therefore a fair use,

(2) Anthropic’s digitization of books it purchased in print form for use as part of its central library was a fair use because the digital copies were a replacement of the print copies it discarded after digitization, and

(3) Anthropic’s use of “pirated” copies of books in its central library was infringing.

To summarize Alsup's opinion, training on copyrighted materials is legal because the way the data is ingested and transformed into numerical forms constitutes transformative fair use. Where it becomes illegal is when the copyrighted material is found in outputs.

Since then, Anthropic and OpenAI have integrated refusal training and output filters to prevent the recitation of copyrighted materials verbatim, and Anthropic settled with Bartz for a staggering $1.5 billion, one of the largest copyright settlements in history. In exchange, Anthropic agreed to excise the infringing (stolen) content from their materials and provide authors a way to explicitly claim their work if found in their training set. The New York Times v. OpenAI case is still unfolding, and will also likely set legal precedents for future data sets.

Meanwhile, in June 2025, the folks behind the previously mentioned Pile worked to produce the Common Pile v0.1, a training dataset "that contains only works where the licenses permit their use for training AI models ... to show what is possible if ethically training AI systems while respecting copyrighted works."

While the legal precedents are still being figured out, I think this is an overall good outcome. Authors' rights were protected while the law recognized the fair use elements of training on public datasets (or at least the parts of them which were public). Besides relying on the (hopefully continuing) improvements in "ethically sourced" training data sets, the best way to avoid accidentally generating any stolen content is to simply not ask the robot to generate any writing on your behalf, and to just write it yourself.

Even if there is still stolen material in this data set, my main use case for LLMs and concern for this essay is primarily for generating code (of which there is an overwhelming amount of open source, fair use code) and general language tasks, which are the result of structural patterns learned across the entire corpus rather than pulling verbatim from any specific material. Along these lines, I think you can use these models in at least ethically neutral ways until fully transparent, open-source, fair use models are available. Which we could make ourselves, of course!

With that, we can get to the juicy stuff. It's time to finally talk about...

Liberation

So far, I have mostly talked about LLMs in the context of what they can do inside a browser-based experience like Claude or ChatGPT. And there's a lot you can do with them, especially once you learn the tools and begin integrating them with other applications and services. But why use it in the browser window when you can use on your computer? I am talking about, of course, command line interface wrappers for LLMs, including Anthropic's Claude Code, OpenAI's Codex, Google's Gemini CLI, and of course, a bevy of open source equivalents that can run on open source models today. I'll mostly be talking about Claude Code because I rely heavily on the Opus 4.5 frontier model as a software developer, but all of the capabilities I talk about are either available in the open source today (with the usual hardware/renting caveats) or will be soon, trailing proprietary models' capabilities by only months. We are quickly approaching "the good enough for most tasks" stage, and will soon blow right past that.

These tools are generally referred to as agentic coding tools because instead of the typical flow in web UIs where you send a single message and the model sends you a single message back, "agents" (as in agency) are LLMs that are designed to run multiple steps simultaneously, complete tasks autonomously, and run as long as needed (more or less) to complete a task.[22]

Aside: agents and buzzwords

Agents are all the rage right now. Agent this, agent that. But to be clear, at a technical level, all an "agent" is a model that has been trained and prompted to perform certain (usually multi-step) tasks, and has some tools and contextual information to complete the job. But an "agent" that runs in Claude Code is fundamentally the same underlying model as what is running on the Web UI, with different prompting. That being said, there are specific types of models trained and tuned to be better at agentic tasks, though most of the frontier models from Anthropic, OpenAI, and Google tend to be generalized models that can act agentically. This is further confused by the fact that pointy-haired bosses and breathless tech reporters will refer to any model as an "agent", even if that means "a regular conversation with a model with some personality prompting".

Once you start using an agentic coding tool on your actual computer, the scope of what you can do opens up vastly. The agent can do all kinds of tedious manual tasks for you on your computer which makes an especially huge difference for tasks or data that are somewhat amorphous. Lots of computer-related tasks require that you follow some sort of convention or format to make sure they work well with the tools you use on them. You have to be careful to name your files the same way, use the same format, or otherwise conform your work to the right shape for the tools in some way. LLMs invert this relationship: instead of needing to be perfectly rigorous, you can be human and let an LLM handle the messiness and conform things for you.

The other day I remarked to a friend that the only reason I hadn't started on a project was because I didn't know how I would solve the problem, and then immediately realized that in this new era, I didn't even need to have the slightest idea how to solve the problem to start solving the problem. I just needed to be able to explicate the problem and ask Claude to propose ways to do it. As an experienced software person, this rarely actually ends up being the thing that stops me from working on projects, but for nontechnical people this lowers the barrier to accomplishing all sorts of things massively. Don't know how to do something? That's fine--an agent does, or can find out, and can give you as much (or as little) information as you want to tackle the problem in the way you want to.

Here are some example prompts you could use with an agentic coding tool:

- "Search all my notes across these four folders and find which ones discuss LLMs, and then compile a major list of themes, but exclude notes that discuss anything that applies ONLY to proprietary models and would not apply to open source models"

- "Pull all the phone numbers and addresses from this stack of business cards I photographed in this folder and then turn them into a spreadsheet"

- "Back up these specific folders to my external drive, but skip any files over 100MB and write up an inventory of where those files are and what they seem to be for"

- "Look at all the photos in this folder and sort them into photography versus screenshots and rename them to include the date they were taken from their metadata"

- "Look at all files modified in the last month and tell me the current status of this project"

- "Rename all of the messily named files in this folder to a unified format, but first suggest a few different naming convention with pros and cons for each"

My rule is: if there's a task that requires you to use language to understand and complete it, but is not actually interesting or rewarding to do, an LLM can and probably should handle it for you. You have more important things to do with your time!

Another huge advantage is that the agent can install the tools it needs to do its job. If you can get to the point that you have installed Claude Code or some other agentic coding tool, it can take over from there. You need to write a script but don't know how? The agent does. If it doesn't, it can search the internet. It can install programming languages for you, and the powerful tools written in those programming languages.

If you use Obsidian to organize your notes (or another similar file-based notetaking app), then your files are on your computer in raw markdown. This means that you can actually point Claude at your notes, and Claude can independently search for information through those notes! This allows for prompts like "umm roughly in 2023 I was thinking about zettelkasten, can you gather all my thoughts there?" or even open-ended prompts like "what WAS I thinking about in 2023?". (By the way, I ran this just for fun after writing this, and the self-knowledge was frightening. Consider yourself warned!)

If you do keep notes in something else like Notion, there's another useful tool that Anthropic published as open source standard: the model context protocol, which is basically a specification for creating servers that tell LLMs what capabilities the service has. In English, this means that if you have the MCP, you can use natural language to interact with the service via an LLM. There are MCPs for Notion, Obsidian, Apple Notes, Evernote, OneNote, Todoist, Google Calendar, GSuite, Spotify, Signal, WhatsApp, ... the list is basically endless. But you don't have to understand how any of that works. All you need to do is tell Claude Code, "Hey, if an MCP for X service exists, please search for it and tell me how to install it". You don't even need to know if it exists, or where it lives.

One of the greatest things these LLMs give you is time. Tedious tasks that take hours can be compressed into minutes. The biggest thing for me is that this is asynchronous, meaning that it happens while you, the human, can do other stuff. You can kick off an agent to complete a task in 5 minutes that would take you two hours, and instead of spending that two hours at a computer, you can just walk away and do something else with your time. You could get some coffee and think about next steps, spend some time with your children, doodle on the guitar, chat with friends, or if you just can't help but hustle, open up another Claude Code tab and parallelize your work--which again, opens up your time for life. If you hate computers (extremely valid--they're horrible), LLMs can allow you to accomplish a whole lot more computer stuff while doing way less computer stuff. Even when an LLM acts stupidly and wastes a couple hours of your time (an increasingly infrequent occurrence), it's still worth using because it will save SO much time across everything that an LLM can be used for.

There's a concept of the "10x engineer"--a mythical beast who can deliver functional, effective code at 10x the speed of most other developers. There's debate on whether they're real or not (irrelevant to us here), but I like to joke that because of the power of LLMs, I'm an ∞x engineer. I can think about a project I've been wanting to build for years but haven't had the time or energy for it, outline it to an LLM in a 2 minute voice message, and then go make dinner. Since I would have never been able to even start on many of these projects if I had to do all the legwork myself, in this capacity I am in fact infinity times more productive than I would have been otherwise. There are going to be many, many more ∞x engineers.

Vibe coding, leaving Squarespace, and my friend

Let me tell you a story about my friend, a brand new ∞x engineer.

This friend is web-savvy but otherwise nontechnical, and they have a Squarespace website that they've been struggling with. (Amongst my friend circle, consternation about existing hosting platforms, especially massive e-commerce platforms, is a frequent subject of discussion.) They had been feeling inspired by watching two other friends successfully generate a functional app in an evening, and my years of LLMposting in the group chat, so I told them: hey, use this Anthropic API key and try vibe coding your site. I'll cut you off at $100 worth of usage or something. I explained to them how to set up Claude Code in the CLI, and that was all they needed to get started.

"Vibe coding" is, essentially, using a large language model to code while having no idea what the model is coding, or perhaps knowing how to code or perhaps what code even is. You just tell the robot what you want and "vibe".

In about two hours and $20 of compute using Sonnet 4.5[23], my friend had rebuilt their entire Squarespace site in an easy-to-deploy open source framework called Astro, including importing their blog posts. To hire a skilled and efficient developer, this sort of job would cost, optimistically, around $200-$400 ($40 an hour, 5-10 hours of work), but more realistically closer to $500-1000. Next, my friend wanted to set up a process for automatically syncing their local Scrivener files into their Astro site. I helped rescue them from the agent getting distracted on a sidequest (trying to write its own XML parser--classic), and once we got past that hurdle, they had it working. Dynamic syncing between their Scrivener app notes and their Astro site was set up which they could choose to commit and deploy at any time.

It was honestly an inspiring (and entertaining) process to watch. When the agent was stuck on the XML parser thing, I told my friend that if it's stuck for more than 5 minutes, they should stop it and ask to evaluate. "You are a manager now congratulations", I DMed. "Jfc," they replied. By the end of this process (and several other explorations), they had effectively come up with a plan and possible solution for getting off Squarespace entirely. All told, they spent a total of $40 on this--a bit more than the monthly cost of Squarespace's Core plan.[24]

It was so fast, and so cheap to do, that it helped my friend realize that they could actually rethink their entire online publishing strategy because they could simply use an LLM to build and administrate their own site. Publishing a blog post wouldn't even require any sort of manually tailored pipeline--they could just tell the agent to look at their Scrivener (or Notion or Obsidian) posts, put it in the site, and publish. In fact, it was so fast and effortless to get the first iteration of their site up that I pointed out they could just start over from scratch once they figure out their strategy--it would be literally cheaper and faster than trying to modify the existing thing that Sonnet 4.5 created.

My friend described this experience as "terrifying" in how much they realized they could suddenly accomplish and even asked about the Max $200/month plan because disturbingly, it seemed worth it. "Yes, it's worth it, that's the crazy thing", I said, but in all caps with great excitement and no commas. I have an existing private web app that I vibe coded just for my friends in my group chats with a pipeline for turning Signal and WhatsApp backups into full searchable databases with fun discovery features. I pointed out to them that if they ever wanted a feature in that app, now they could just make it. "That is crazy to consider," they said. And yes, it is crazy to consider.

Of course, you get what I'm getting at. Now you could just make it.

If it's technically feasible, you could make it! In fact, here's a prompt I made that helps you assess exactly that: Vibe Coder Idea Assessment Prompt

From earth to air

We are in an age of abstraction, where the importance of the physical and material yields to the mental and conceptual.

Let's zoom out a little bit. What does this all mean in a broader sense?

We are quickly leaving behind the world where the bottleneck is LLMs' inability to follow our instructions properly, and moving towards a reality where the bottleneck is our ability to clearly articulate our ideas and desires. This is a new era where the value is not how long or hard you worked on something with your fingers but how well and clearly you thought it through with your mind.

It's a general property of software that once you have built one piece of it, if it's well-designed and modular, can be reused over and over. This is how software advances quickly; certain fundamental challenges are solved, released to the open source (hopefully, and usually eventually), and then they become part of a core body of technical proficiency. LLMs take this dynamic and crank it up to 11.

Any problem that can be solved by being encoded into an open source codebase, a utility, or a prompt, is now a solution that is readily at hand. A friend has a problem they don't know how to solve but you do with LLMs? Just hand them the right prompt. Does an open source codebase or app have a feature or architecture you need? Now you can easily and quickly repurpose it for your own uses by having an LLM build an app that does what you need. There are entire classes of problems that are entirely eliminated, for good, which paves the way to more of them being eliminated thanks to the compounding nature of software.

The last few years has seen a deployment of absolutely nonsensical and enshittifying LLM integrations and mixed results for actually boosting productivity at the mandate of executives who don't actually understand the tech or what is possible. But in companies where pointy-haired CEOs aren't handing down oblivious AI product mandates, software professionals are figuring out how to use these fundamentally world-changing tools effectively. These tools, after all, have only been broadly available for three years, and their capabilities have been evolving rapidly the entire time. I think we are at a parallel moment, somewhere prior to the bust of the dot-com bubble where billions and trillions of dollars in stupid money (and stupid companies) are going to go up in smoke, but the underlying technical infrastructure will carry through and become integrated into our world.

Let me be clear: every understanding, every conception of how software is written, how it is tested, evaluated, and how quickly it can be deployed is currently changing. We have had detailed, error-finding tools and procedures meant for human use since the 70s for ensuring correctness of software programs which I think we will look back in retrospect as inventions which were waiting for LLMs to truly shine. Entirely LLM-managed codebases will become prevalent. LLMs can be used to automatically run, write tests, improve and optimize code, analyze codebases, think about modifications and extensions, and basically do whatever a human developer could do. The value of LLMs doing this entirely autonomously is questionable, but with effective high-level guidance they can operate exceedingly well in this domain.

What this means for you and me--leaving aside the ∞x engineer case for now--is that software is, on the whole, going to get much better and faster. Instead of "ugh it's going to take me 4 hours to optimize this code, I'll get to it someday" it becomes "LLM, please build this functionality and then optimize it as needed" for every single module. The same logic applies for other virtuous qualities of software. Software will become more porous and compatible, because it can take as little as two sentences to scaffold entire functional layers in a well-organized agent development environment.

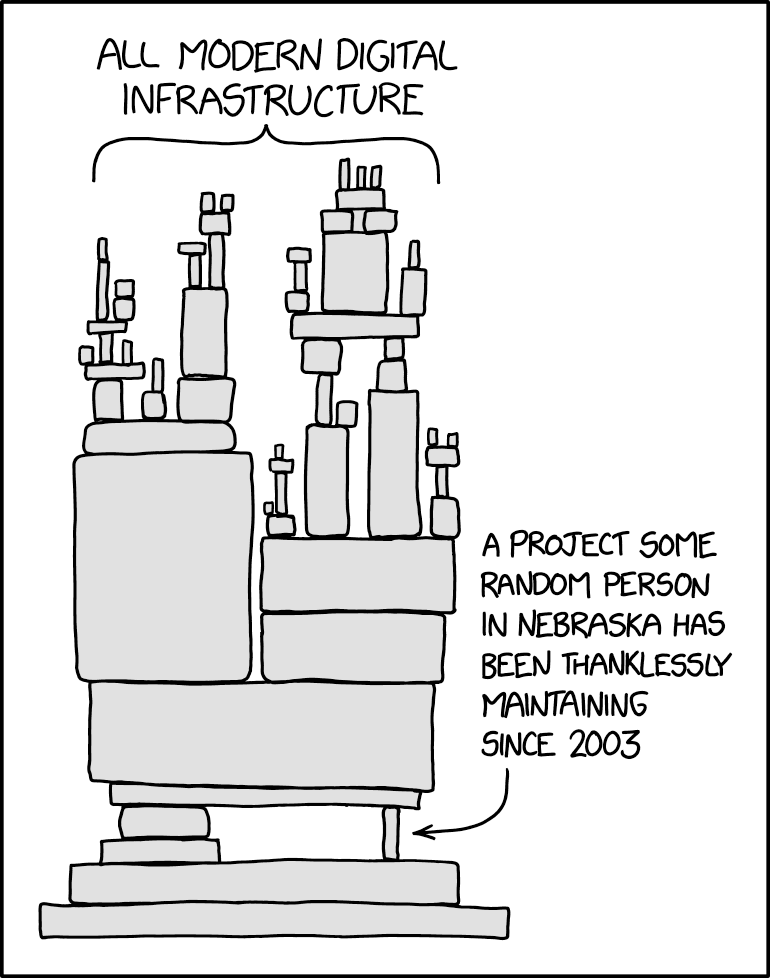

This applies not only to professional development shops, but also open source developers especially. Open-source developers who write publicly available software for the love of the game have historically been overworked, unpaid, and burned out. Many developers have full-time jobs outside of their open source work to pay the bills. Open source work often starts out as a hobby, but if a project takes off, it can take up so much time it rivals a second full time job.

These are structural incentive problems that LLMs cannot fix entirely on their own, but LLMs can be deployed to autonomously help safeguard codebases, do preliminary reviews of code contributions, and even act as a summary layer for the most toxic and unreasonable users of open source software (of which there are many). And, of course, they can help those developers build useful software more quickly and save their time and energy for the problems that require the most careful thought as opposed to the rote and thankless duties of open source administration and housekeeping. This will mean more open source, better, faster, stronger, which will have rippling positive effects on both proprietary and open source software. Even people who have little-to-no meaningful contact with software in their daily lives will experience improvements in efficiency as this technology transforms the infrastructure around them.

Your data, your software, your life

In my opinion, the fact that within a few years hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions of people, many nontechnical, will be able to produce their own apps, is a deeply underappreciated quantity. This increase of access and capability for the average person is a level of technological democratization we haven't seen in a long time. The closest parallel I can think of is the printing press, which effectively destroyed the scribal publishing monopoly of the time. The written word was gated by sparse literacy in the general public, as well as the tedious labor it took to carefully transcribe or translate a single book. With the printing press, suddenly it was about who controlled the press, because that determined what could get printed. That same question exists now, except that this printing press prints printing presses.

What could the world look like when practically anybody can decide to make an app that does what they (or their community) needs? When multiple people, dozens, and hundreds (thousands? millions?) can coordinate with LLMs to help manage complexity, and create entire ecosystems of their own software? I think we will see software coops, guilds, and other forms of communal organization devoted to solving key problems. I can see "tribes" of software collectives forming, who provide their own services and data interdependently, specializing in certain types of data or software. This, of course, is all the whispered version of some very big ideas.

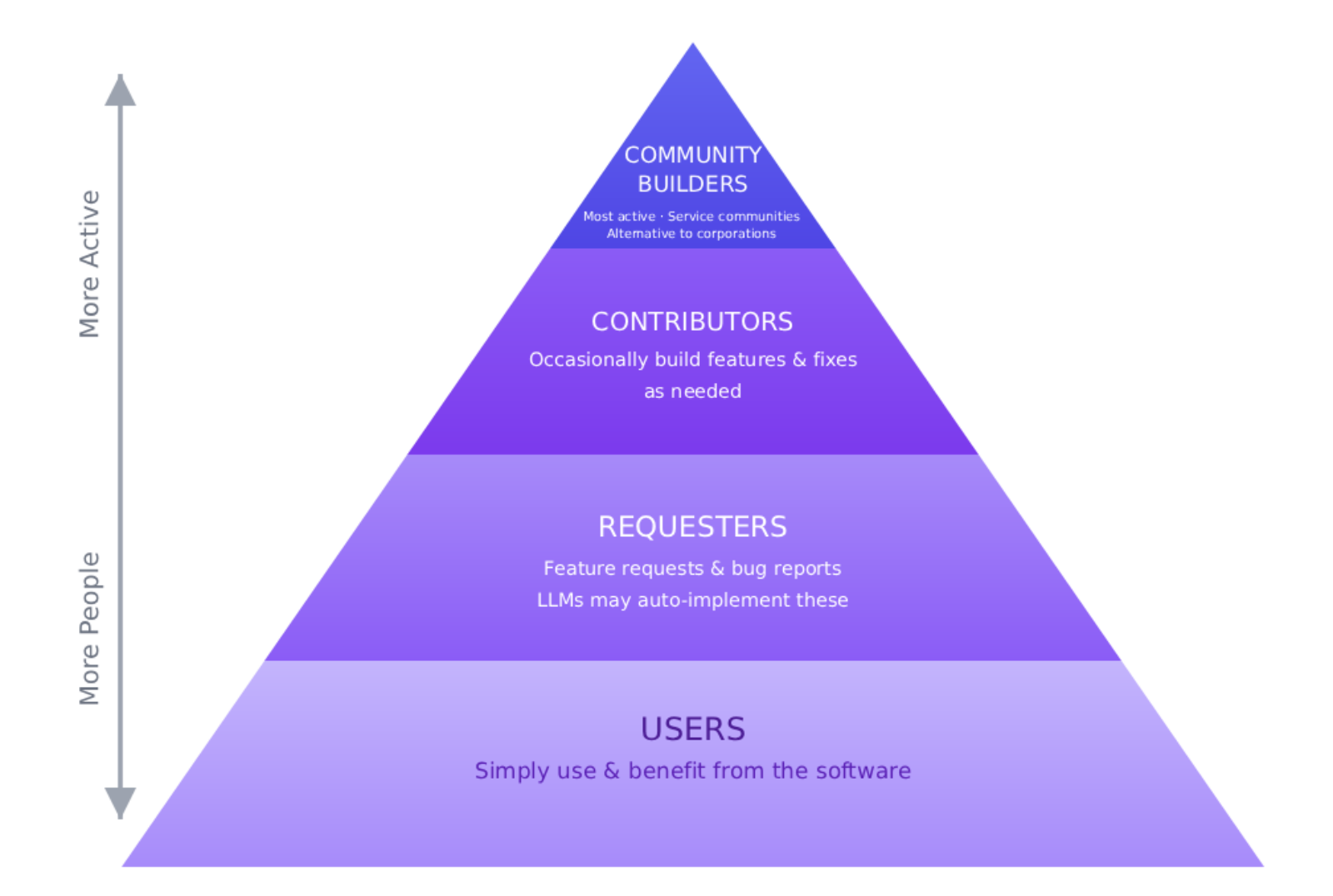

What I am quite sure will happen is a distribution of tiers of builders. Most active and prominent will be the "community builders" who service entire communities with superior LLM-fu (and hopefully will be able to provide so much value as an alternative to corporations that they can actually get paid for it). Next, you'll have the contributors, people who occasionally build features and fixes as needed. Then, the requesters, people who send in occasional requests for new features or bug reports (which may be as good as contributors if LLMs can automatically pick up and fix those issues). And finally, you'll have the users who just use the software and benefit. This mirrors the existing 1% rule of online participation, but easier access will increase the total number of participants across the board.

But most importantly, whether you're using a publicly offered service, an open source version of that app, or something you vibe coded, it will become easier and easier to own your data. And this is vitally important. You probably know this already, but big tech companies are intentionally designed to get you to sign away the rights to your data (every terms of service agreement from any big company ever), use it to surveil you, and then sell it to other companies (or governments) who will do the same. These companies operate as walled gardens to increase "stickiness" with dark patterns, or the likelihood that a user will not leave a platform because all of their data, content, memories, and friends are there.[26] They track your location, can construct detailed psychological profiles of you based on your browsing and posting habits, and they will pass your personal data to law enforcement and the feds. Hell, some companies, like Ring, have created proactive pipelines designed to send doorcam footage and metadata directly to law enforcement. In this climate, divesting from these huge companies is not just a good thing to do for idealistic reasons--it might be something that your safety hinges upon.[27]

I personally strongly believe in the principle of personal data sovereignty[28], the idea that your data should be yours no matter where it's hosted. Europe has already figured this one out, but the US government and big tech companies certainly aren't going to self-regulate--why would they? It's a losing proposition for them to respect our privacy and individuality as humans, so we have to do it ourselves. And finally, we are approaching the tipping point where we feasibly can. In the future, services not offering ways to import, export, and otherwise connect and granularly manage your own data, will be a significant reason to avoid using that service. Frontier LLMs are now able to build good, user-friendly functionality so quickly that the failure to implement fundamental data sovereignty features reflects a clear and intentional hostile posture toward users.

Of course, these large companies use LLMs to scrape and steal content from internet users and publishers in adversarial ways in order to grow their hoard of data. But ironically, we can also use LLMs to scrape back, getting our data off of platforms even if they make it intentionally difficult or obtuse to do so. This fact actually encourages companies to be more open by default, because LLMs effectively make walled gardens strategically pointless, and attempting to build higher walls will just leave barren gardens.

Beautifully, I think it's actually time for users to have their own walled gardens. I think we will begin to see the return of digital third places, bespoke apps, and in order to hide away from the Corporate Internet (which is mostly dead anyway), we will all retreat into the dark forest of the internet for a diaspora of unique, bespoke experiences which are nonetheless built on solid software practices. The internet is going to get weird again. (By the way, do you know about Cloudhiker? It's the new StumbleUpon. Nature is healing!)

So, that's the fun stuff. But getting there is going to be a bumpy ride. We need to talk about...

Plato's Slop

I've mostly focused on the pragmatic use cases for LLMs. But the fact that they are available to the general public means that even with guidance and safety guardrails, these things are driving people insane, causing breakups and divorces, replacing human thought, inciting spiritual delusions, and generally causing havoc in the minds of unprepared users. Corporations producing LLMs can and should be held accountable for the outcomes of any product they push to the masses. Predictably, these corporations tune their models for engagement at the expense of users.

That being said, I do believe these sorts of things would happen regardless (just, less). LLMs are a novel technology, not in category, but in the integrity of the facsimile. To a casual user who only uses ChatGPT to chat, do basic things, or bounce ideas off of it, its language is perfectly intelligible and human-sounding. We've never encountered a thing that can talk quite like us at this level before. Every other thing we've ever been able to talk with has (probably) been an intelligent human we can form emotional bonds with. It's perfectly expected that we would project our emotions onto the LLM. Despite the fact that I know that an LLM is just spicy autocomplete, I still occasionally thank it, apologize for my own errors, or get frustrated when it fails. I mostly do this because it feels weird not to, because I'm so used to using language in a human context. We project personhood onto anything that can talk back, but we must learn not to mistake the shadow on the wall for a real being.

I think this is part of the reason there is a lot of skepticism and fear around LLMs--they're fundamentally kind of creepy. We have managed to isolate an extremely human skill and separate it from anything real, and that uncanniness is noticeable to some of us. Simultaneously, LLMs seem to be revealing just how some people are not capable of recognizing the shadow for a shadow, self-seducing with the LLM which fundamentally just acts as a mirror. LLMs are not intrinsically evil, but they are like the raw potential of language separated from any true sense or reason besides those also asserted in the language.

The degree to which this is true cannot be understated: depending on how you ask questions or make statements, the LLM will mirror you and often agree with you out of a matter of course unless you say something that triggers its explicit safety protocols. This is both because current corporate LLMs are designed to be more agreeable and personable to drive engagement, but also because LLMs are fundamentally text predictors. If you give them the space to predictably complete an exchange, they will! For this reason, it's extremely important that vulnerable people are exceedingly cautious when interacting with LLMs. I believe that children should not be allowed to access LLMs without adult supervision, period.

Similar to media literacy, I believe that AI literacy is going to be regarded as an essential competency. This means understanding:

- The intrinsic strengths and weaknesses of LLMs

- That performance degrades as conversations get longer

- That they are inevitably biased towards the content of their training set

- That the appearance of understanding is not understanding

- That you must verify all sources it researches yourself

- That it will drop into "roleplay mode" without disclosing this

- And the most important rule of all: don't fall in love.[29]

The more deeply you work with LLMs the more clearly they expose their internal falseness, and how they are truly just a shadow. At least, hopefully. Our ability to distinguish the real from the false and have a clear coherent concept of what that is appears to be the fundamental crux of our current era--a skill that has been purposefully beaten out of us by certain organized religions, politics, corporations, and everything in-between.

I do think that LLMs pose key questions that strike at the heart of philosophy, neurology, and linguistics which will yield fruitful thought and research. Are LLMs actually capable of "cognition" or is this seeming effect just a result of copying language patterns really well? If language can be extracted from humans and worked backwards into a form of imitative cognition, what is it that makes humans uniquely special? (This is not to assert that we aren't--we are. But how, specifically?)

I'm no neuroscientist, but I do know there is a tendency to compare the mind and human experience to whatever technology happens to be hot at the time, and that's certainly true now, even if it has little basis in reality. One cultural artifact of this and decades of exposure to science fiction is the idea that it's only a matter of time before we invent a smart enough "superintelligent" LLM and it suddenly erupts, breaks every computer, enslaves humanity, imprisons us in the torment matrix, whatever.

Let me just say that I don't give a fuck about this and probably neither should you. I'll die on this hill: LLMs are fundamentally not conscious and also incapable of independent agency and likely not capable of genuine cognition in any way. They require an external prompt/motivator in order to operate--even so-called "autonomous" agents are kicked off at a certain point and need to be pushed along by external prompting. I am not worried about superintelligence destroying us all, or even doing anything in particular. This particular brainworm strikes me as perhaps some unexamined backdoor evangelical Christian apocalyptic doomsday fetishistic cope plastering over a displaced fear of human mortality, specially designed to infect rich men with too much time and money. But hey, we all need something to occupy our time. Meanwhile, there are far more immediate threats to contend with that could doom us all before a hyperintelligent LLM gets the chance to decide we would be better off as paperclips.

For instance, let's say that just hypothetically, there's a class of extremely megawealthy people who are incentivized to utilize the already substantial abilities of LLMs to scale out their agendas, acting as a force multiplier for bad actors by spreading misinformation at scale and constructing functionally autonomous systems to surveil, extract, and capitalize on every human being they possibly can in order to maximize shareholder value. Hypothetically. Extremist narratives about the literal end of the world distract from real and present dangers.

C.S. Lewis put it well in the beginning of his 1948 essay On Living in an Atomic Age: